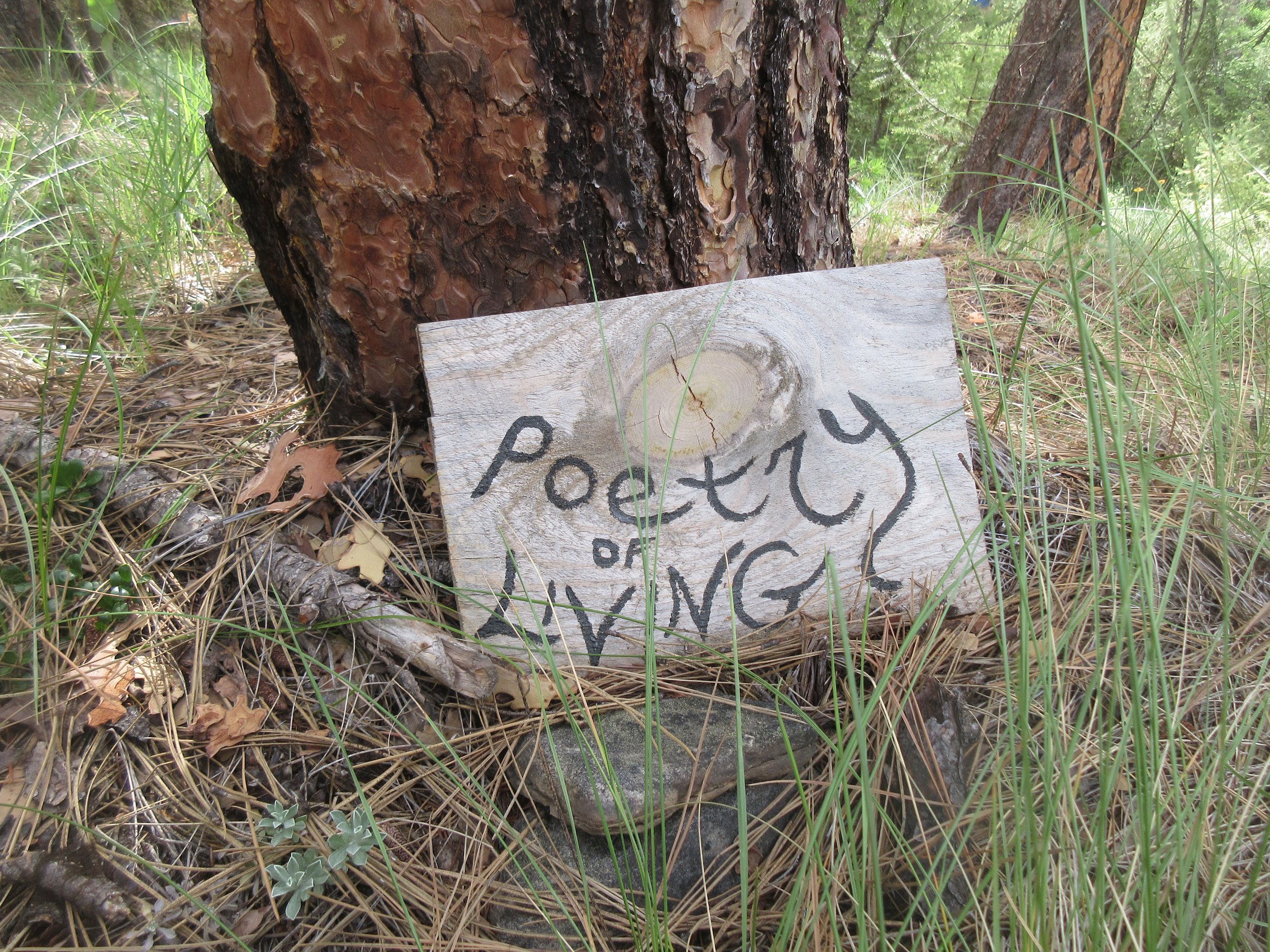

Poetry of Life

The poetry of life involves tending well to the logistics of living while also practicing to fall in love with the world, follow our heart, and savor the present moment at hand.

Conveying the poetry of living in the woods without romanticizing it is no easy undertaking. I’m not even sure it’s possible. But as a writer, a poet, and also what I consider to be a practical realist, I’d like to give it a try.

Anything that even remotely sounds interesting or appealing can be subject to over-inflating about how it’s the best thing ever. While I consider myself a romantic, the thought process of romanticizing is different. Romanticizing involves being untethered from the nature of reality in some way. It means getting caught up and swept away in fantasy ideas about notions that are either wildly un-obtainable or just basic non-sense. I am not a fan of romanticizing. In fact, I would got further and say that I am a big fan of specifically not romanticizing. (Related side note: rom-com movies masquerade as light-hearted entertainment but in reality are the kill-joy of us all. Okay. End of quick rant.) If we can romanticize and know that’s what we’re doing that’s cool, but often we’re not consciously aware of it, which is when trouble can brew.

It’s easy for some folks to romanticize where are how we’re living here at Empty Mountain. And that’s because it’s easy for all of us to put on a pedestal things we don’t have direct contact or experience with. It’s a little common thing us humans do. When folks think about living off-grid in the woods, it’s easy to think about the loveliness of the trees and not the peskiness of the bugs; the heavenly scent of pine and not the sap you sometimes sit in and will never fully wash out of your clothes; how great it is to get your electricity needs met through the sun filtering through solar panels and not about the steep learning curve required to learn a whole new system of technology; the comforting feeling of using a woodstove as your heat source and not the ongoing collection and chopping of wood. But what I’m calling the Poetry of Life (POL) includes everything I just mentioned. Poetry can exist without romanticizing, without reaching into the realms of fantasy and fairy tale.

When I talk about the POL I don’t mean one that’s lived in the company of non-reality, but expressly in the true heartbeat and full breath of it. The POL involves tending well to the logistics of living while also practicing to fall in love with the world, follow our heart, and savor the present moment at hand. It involves seeing the realness, challenges, hardships, and difficulties that exist without losing sight of the splendor, joy, wonder, and nourishing elements that are also part of the equation of being alive and human.

The POL is not about shirking our responsibilities at work or sidestepping our chosen obligations. It’s not about daydreaming or pie-in-the-sky thinking. The POL is about doing our work and taking care of the things we all need to take care of, but not at the expense of disconnecting from such things as rest, self-care, play, beauty, spiritual practice, and spending quality time with the people we love.

Here at Empty Mountain, and I’ll speak for myself and not on behalf of Mike (cuz we-speak has its place but should also, in my opinion, be limited), the POL is in full-swing and on verdant display. Remote woods living suits me well. On the literal poetry front, I read and pen poems in the early morning when I rise. And on the metaphorical POL front, I take pleasure in and get satisfaction from such things as hauling water and chopping wood. I pause regularly to revel in the light singing through the trees, illuminating everything I see in a wash of golds and greens. I watch and listen to the birds. My pace of movement is slower here than it was when we lived in town. And I really really like that.

I work part time a job I get paid to do. I cook. I siphon water from one place to another and carry it around in buckets. I gather sticks and sometimes chop wood. I make sure we have food to eat and I move the solar panels around throughout the day to track the sun. I keep one eye on the logistics and practicalities necessary and required for my chosen way of life, and one eye on the poetry of living.

The woods are so very lovely. And. How we’re living also involves a lot of hard work. At times it’s been hella stressful and overwhelming. I’m almost tempted to say that it’s more work living how rustically we’re living than it was when we lived in town, but I really don’t think that’s true. I think that’s just a conditioned response we’re collectively led to believe is true but isn’t (at least not necessarily). Really it’s just a different kind of work. And, for us, it’s work we’re more willing and glad to do. We’d much rather (and yes, the we-speak applies here) be tired and sore at the end of the day from building things on site and hauling wood & water around than from working a 10-hour shift at a soul-killing job just to pay the mortgage.

And, in what feels like an ironic twist, personally speaking, I feel more connected to the world and to people living out here in the woods than I did when living in town. My heart is much less constricted and bogged down surrounded by the robust community of trees, plant life, and animals. In town it was more of a challenge not to armor up and guard my heart in an effort to conserve and protect my energy. Out here my heart is growing, opening, and expanding.

When living in town, the external surroundings were always adding stimulus in the form of noise, advertisements, people, production, movement, and the industry of all that it takes to make a town possible. But I didn’t fully realize or appreciate just how much life-force energy I was expending in the direction of self-regulation and staying balanced in the midst of so much sensory input until we moved into the woods. Out here, instead of energy going out, there is energy coming in. Nature is a powerful source of nourishment and healing. Of course, in-town living didn’t only involve energy going out. There was energy coming back in, too. But the ratio of energy going out to energy coming in was something akin to 80/20 or 70/30. Out here, for me, the numbers are reversed.